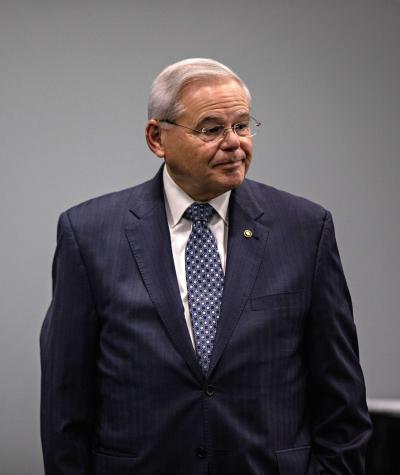

When Senator Robert Menendez was indicted on federal corruption charges on September 22, 2023, the shocking details revealed by the allegations seemingly had no end. Wads of cash totaling almost half a million dollars stuffed into clothing pockets and closets.

A $60,000 car gifted in the aftermath of a fatal crash caused by Senator Menendez’s wife. And more than $100,000 worth of gold bars, some of which were imprinted with serial numbers traced back to the man alleged to have provided at least some of these gifts in exchange for official acts.

Why did it take a second federal prosecution to reveal what is apparently blatant corruption in the so-called “world’s greatest deliberative body”? Clearly federal investigators have been on Menendez’s trail for some time (Menendez was also prosecuted on corruption charges in 2015).

But these repeated offenses beg the question: Is the Senate incapable of finding and rooting out potential corruption before it becomes a crime?

The answer seems likely to be yes. Unlike the House of Representatives and every major executive branch agency, the Senate has no independent body that is dedicated to investigating ethics violations, fraud, waste, or abuse.

The ethics process in the Senate is a black box: A concerned citizen or Senate colleague could file a complaint with the Senate Select Committee on Ethics (Ethics Committee), but there is no public process for bringing that complaint through an investigation and to a resolution.

The Ethics Committee, while bipartisan, is still comprised of members of the Senate tasked with investigating and punishing their colleagues, on whom they rely for getting critical votes for legislation in a closely divided chamber.

This system does not work. A recent study found that of the 1,523 complaints sent to the Senate Ethics Committee since 2007, zero resulted in any formal disciplinary sanctions over 15 years. This is a pervasive ethics enforcement problem in the Senate that has flown under the radar for far too long, and it will only become worse unless we put a stop to the status quo of self-policing.

Would a better system of ethics enforcement, combined with more robust disclosure laws, have prevented all the corruption we saw laid bare in the Menendez indictment? Probably not; ethics laws and good enforcement, while essential for protecting the public’s trust, are not a panacea for all the government’s corruption woes.

But the status quo simply is not good enough. The public has no way to trust ethics investigations are being done in the Senate, and the instances of ethics wrongdoing that eventually come to light are only publicized because they rise to the level of a serious federal crime.

The public should be unwilling to accept that if their Senators are not committing transgressions that would land them in federal prison, everything else is fine.

The gold bars and the expensive car may have raised red flags — if there was any reliable place to raise them. It’s possible a constituent who followed the news of the fatal car crash and then saw Mrs. Menendez shortly after driving around in an expensive new vehicle may have had some questions, but nowhere really to deposit those questions.

The gold bars, while reported in amended financial disclosures, also may have raised the suspicion of eagle-eyed watchdogs — who could have filed a complaint with the Ethics Committee, a task that is as good as or worse than shouting allegations into a black hole.

The Senate needs its own independent entity for ethics investigations. Such an entity will not prevent all bad actors from committing corruption related crimes. But it is the bare minimum the Senate can do to start engendering a culture of ethical behavior and eschewing the status quo that has led to some of the most shockingly blatant allegations of corruption seen at the federal level in recent years.